I just returned from delivering a talk at the Project Management Institute Spring Symposium in Michigan. The main message I had for this group was while many organizations have ample skill in solving problems and managing projects effectively, the untapped opportunity comes from doing a better job in selecting the right problem to solve. Most problems are fuzzy, having many facets to them. In today’s world where we value speed, efficiency, and cost minimization we can too often rush to solving problems without taking time to amply understand them, and their various root causes.

I just returned from delivering a talk at the Project Management Institute Spring Symposium in Michigan. The main message I had for this group was while many organizations have ample skill in solving problems and managing projects effectively, the untapped opportunity comes from doing a better job in selecting the right problem to solve. Most problems are fuzzy, having many facets to them. In today’s world where we value speed, efficiency, and cost minimization we can too often rush to solving problems without taking time to amply understand them, and their various root causes.

Sometimes slowing down, being more exploratory, and striving for deeper understanding before launching into problem solving can pay big dividends.

In the Creative Problem Solving Process (See Slowing Down to Move Fast), the first important aspect of understanding the problem better, called “problem formulation” is to collect facts and information, driving us to ask more questions and consider more aspects of the problem.

Some of this comes from doing research on Google, or collecting readily available historical data. However data alone can often present a fairly limited view of the situation. So, we always like to challenge organizations to add to their empirical data, intuitive information that comes from consumer observations and interviews. David Kelly (founder of design firm IDEO) likes to call this process one of “empathetic observation”.

Many technical people immediately presume that we can’t learn from ordinary people who are not experts in the technologies related to our business. One of the participants in my session this week quoted Henry Ford who once said: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” Yes, it’s true that most people can’t imagine something they have never before seen or experienced. (If you asked people 15 years ago how they wanted to communicate, it is doubtful they would have described an iPhone 5.)

HOW DOES EMPATHETIC OBSERVATION WORK?

So if we can’t ask consumers what they want from us, how do we gain the understanding we need to create breakthrough innovations? The art of empathetic observation is a means to observe and listen to customers as they

– Make their own purchase decisions

– Use our products or services

It’s not so much about interrogation, more like looking over their shoulder while trying to imagine what they are thinking and feeling as they do.

I like to think about it as asking open-ended questions that cause them to talk about their lives in as personal a manner as they feel comfortable and then we have to do the “heavy lifting”. We need to listen for the current and future possible intersection points between their lives and our products/services. We are “tuning in” to the things that cause our interviewee joy, frustration, fear, or anger – looking for unmet needs that we imagine our organization might be able to do something about.

STARBUCKS CASE

Imagine the coffee retailer Starbucks, trying to solve the problem: “How Might We Better Grow Our Same-Store Sales?” As you can imagine growing only by adding more brick and mortar is expensive, so if we could somehow increase traffic in our EXISTING stores, wouldn’t that be far less capital consuming? We can increase store sales by growing traffic, or by getting people to spend more each time they come by.

So to explore this question we create 2-person interview teams (one to ask questions, and one to write and help observe) and we begin to interview current Starbucks customers asking them questions like:

– Tell me about a typical week in your life.

– What are some of the biggest challenges you are experiencing in your life right now?

– What are the things that you feel you need help with that would make the biggest difference for you?

– What are the things that currently cause you to visit a Starbucks outlet?

– When you do stop in, tell us what the experience is like for you.

– Etc.

Notice that nowhere are we asking the consumer directly what they want Starbucks to create for them. We are just getting them talking about their lives as we try to understand them better.

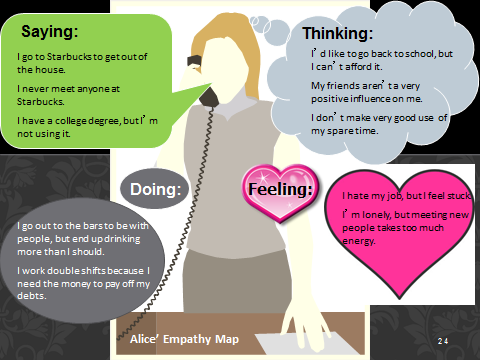

When the interview is completed, our interview teams try to summarize the highlights of their conversation on a simple one-page template called an empathy map (see graphic at the left). The map is divided into four sections: Quotes and Defining Words (3-5 bullet points of significant things the interviewee said); Actions and Behaviors (what they described that they did or how they behaved in their life), Thoughts and Beliefs (what we sensed they might have been thinking but never articulated to us during the interview); and Feelings and Emotions (what we imagine they might have been feeling when they were describing their life that they did not explicitly share).

When the interview is completed, our interview teams try to summarize the highlights of their conversation on a simple one-page template called an empathy map (see graphic at the left). The map is divided into four sections: Quotes and Defining Words (3-5 bullet points of significant things the interviewee said); Actions and Behaviors (what they described that they did or how they behaved in their life), Thoughts and Beliefs (what we sensed they might have been thinking but never articulated to us during the interview); and Feelings and Emotions (what we imagine they might have been feeling when they were describing their life that they did not explicitly share).

Now the first two sections are relatively easy to create as they come from direct quotes we took from the interview. But it is the last two quadrants that are most interesting since we are asking the interviewers to be amateur psychologists to go beneath the specific words and deeds to the underlying motivations. This requires our empathy, plus a little instinct and intuition.

To give you a better idea of this concept in practice, here is an empathy map (see below) for one of our Starbucks Case interviewees, we will call “Alice”. As you read the summary points on this map, you can begin to imagine how the actual interview went. The interviewers in their summary seem to be “tuning in” to a host of issues related to Alice’s unmet need to meet new and different people in her life who might be a better influence on her. You can sense that she may be looking for new people who can become personal friends, as well as professional contacts that might help her in her career.

When the interviewers presented their Empathy Map summary, they talked about how the sensed Alice was somewhat shy, and that “breaking the ice” with strangers was one of her challenges.

When the interviewers presented their Empathy Map summary, they talked about how the sensed Alice was somewhat shy, and that “breaking the ice” with strangers was one of her challenges.

Now I imagine that two different sets of observers who witnessed the session with Alice might have summarized the interview differently. That’s because we all observe and listen with different lenses based on our own personal biases and experiences.

But when we collect interview summaries from multiple groups and interviewees, a diverse array of observations start to emerge that can create a rich fodder for subsequent problem definition and idea creation steps in the Creative Problem Solving Process.

In a sense, each of the separate bullet points captured on the empathy map is a new problem to be solved for Alice. To me this is an interesting example because this leads Starbucks to think not about another variety of beverage product, but to how they might engineer their store environments in new ways to help Alice and the other customers like her.

Effective brands make emotional connections with consumers who use them. One way we can do this is by being relevant in the world of the people we serve, making a difference that really matters. The empathy mapping example described here will help you and your colleagues go deeper in your understanding of the problems in front of them as you search for breakthrough innovation possibilities.

Other Resources

Converting Empathetic Observations Into Solutions, by Len Brzozowski, lenbrzozowski.wordpress.com

IDEO and The Art of Innovation: The Role of Listening in Consumer Product Development, from businesslistening.com

Spark Innovation Through Empathic Design, by Dorothy Leonard and Jeffrey F. Rayport, Harvard Business Review

How to Use an Empathy Map, from Stanford’s d-School

Empathy Map, from Gamestorming: a playbook for innovators, rule-breakers and change makers